Learning Effectiveness Checklist: Evidence-Based Strategies for Retaining More, Learning Faster, and Avoiding the Study Habits That Waste Your Time

In 2006, cognitive psychologists Henry Roediger and Jeffrey Karpicke published a study that challenged one of the most deeply held assumptions about learning. They gave students passages to study and then tested them under different conditions. One group read the passage four times. Another group read it once and then took three practice tests on the material. When tested one week later, the students who had practiced retrieval (testing themselves) remembered 50 percent more than the students who had re-read the passage multiple times.

The finding was striking, but it was not new. Researchers had been documenting the testing effect--the principle that retrieving information from memory strengthens memory more effectively than re-studying the same information--since at least 1917, when Arthur Gates published the first systematic study of retrieval practice's effect on learning. A century of research has confirmed and extended the finding: testing yourself is one of the most powerful learning strategies available, consistently outperforming the strategies that students most commonly use, including re-reading, highlighting, and summarizing.

This gap--between what learning science has established about effective learning and what learners actually do--is the central problem of educational practice. The strategies that feel most effective (re-reading feels productive, highlighting feels active) are among the least effective, while the strategies that are most effective (retrieval practice, spaced repetition, interleaving) feel more effortful and less productive. This checklist bridges that gap by providing an evidence-based framework for evaluating and improving learning practices across any domain.

Part 1: The Science of Effective Learning

What Makes Learning Effective?

Decades of cognitive science research have converged on a set of principles that reliably produce durable, transferable learning. These principles are not domain-specific--they apply to learning languages, mathematics, medicine, programming, music, history, and virtually every other skill and knowledge area.

Active retrieval. The single most effective learning strategy is actively retrieving information from memory rather than passively reviewing it. Retrieval practice--testing yourself, answering questions, recalling information without looking at the source--strengthens memory traces and improves the ability to access information when needed. This is the testing effect, documented in hundreds of studies across decades of research.

Spaced repetition. Distributing practice over time produces dramatically better long-term retention than concentrating practice in a single session. Reviewing material one day after initial exposure, then three days later, then one week later, then two weeks later produces far better retention than reviewing the same material four times in a single session with the same total study time. This is the spacing effect, first documented by Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1885 and consistently replicated since.

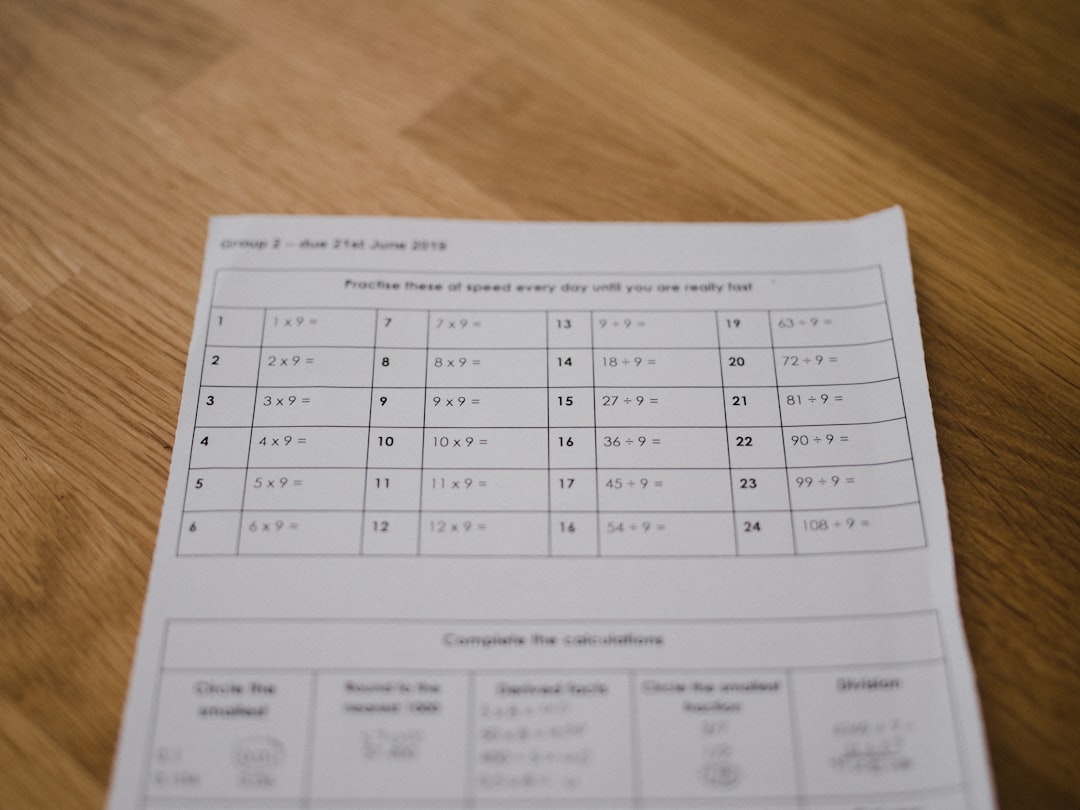

Interleaving. Mixing different topics, types of problems, or skills during practice produces better learning than practicing a single type repeatedly (blocking). A math student who interleaves algebra, geometry, and statistics problems during practice will perform better on a test than a student who practices all algebra, then all geometry, then all statistics--even though the interleaved practice feels more difficult and less productive.

Elaboration. Connecting new information to existing knowledge by explaining, comparing, contrasting, and generating examples deepens understanding and improves retention. Simply asking "Why does this work?" or "How does this relate to what I already know?" produces learning gains because it forces the creation of meaningful connections rather than isolated memorization.

Concrete examples. Abstract concepts become more understandable and more memorable when illustrated with concrete, specific examples. A student learning about supply and demand who studies the abstract curves and equations will retain less than a student who also works through specific examples: "What happens to the price of umbrellas when a rainstorm is forecast?"

Immediate feedback. Learning improves when errors are corrected quickly. Delayed feedback allows incorrect understandings to consolidate, making them harder to correct later. The most effective learning environments provide feedback within seconds or minutes of performance, not days or weeks later.

Deliberate practice. Improvement in complex skills requires practice that is focused, effortful, and targeted at specific weaknesses. Simply spending time on an activity does not produce improvement; the practice must be structured to push beyond current ability, provide immediate feedback, and focus on the specific components that need improvement.

Part 2: The Learning Effectiveness Checklist

Check 1: Am I Using Active Recall Instead of Passive Review?

What to check: After studying material, am I testing myself on it (active recall) or simply re-reading it (passive review)?

Why this matters: Re-reading creates a feeling of fluency--the material seems familiar, which the brain interprets as understanding. But familiarity is not the same as learning. Recognizing information when you see it is far easier than producing it from memory, and it is the production from memory--not the recognition--that most real-world tasks require.

Research by Karpicke and Blunt (2011) compared retrieval practice to elaborative studying (creating concept maps while studying) and found that retrieval practice produced 50 percent better performance on a delayed test, even though students who created concept maps predicted they would perform better. The subjective feeling of learning was inversely related to actual learning--students felt like they learned more from the less effective method.

How to apply it:

- After reading a chapter, close the book and write down everything you can remember without looking. Then check what you missed.

- Create flashcards and test yourself rather than re-reading notes.

- After a lecture or meeting, spend five minutes writing down the key points from memory before reviewing your notes.

- Use the "blank page" technique: before studying, write everything you already know about the topic on a blank page, then study to fill gaps.

Check 2: Am I Spacing My Practice Over Time?

What to check: Am I distributing study sessions over multiple days/weeks, or concentrating all practice into a single session?

Why this matters: Cramming (massed practice) produces short-term retention that fades rapidly. Spaced practice produces long-term retention that persists for months and years. The spacing effect is one of the most robust findings in cognitive psychology, replicated across hundreds of studies, multiple decades, and diverse populations and learning domains.

The mechanism is that forgetting between sessions creates "desirable difficulty"--the effort of retrieving partially forgotten material strengthens the memory trace more effectively than effortless review of fully available material. Counterintuitively, a small amount of forgetting between study sessions actually improves long-term learning.

How to apply it:

- Schedule multiple shorter study sessions over several days rather than one long session.

- Use a spaced repetition system (SRS) like Anki, which algorithmically schedules reviews at optimal intervals.

- After learning something new, plan review sessions at expanding intervals: 1 day, 3 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month.

- Do not wait until you have forgotten something completely to review it. Review when the material is partially faded but still retrievable with effort.

Check 3: Am I Interleaving Different Topics?

What to check: Am I mixing different types of problems, topics, or skills during practice, or am I practicing one type at a time?

Why this matters: Interleaved practice feels harder and less productive than blocked practice. Students who interleave algebra and geometry problems feel less fluent and predict lower test performance than students who practice blocks of each type. But on actual tests, interleaved practice produces significantly better performance because it forces learners to identify which type of problem they are facing and select the appropriate strategy--skills that blocked practice does not develop.

Rohrer and Taylor (2007) found that interleaved math practice produced 43 percent better performance on a delayed test compared to blocked practice with the same total practice time. The effect has been replicated across mathematics, medical diagnosis, art classification, and other domains.

How to apply it:

- When studying for an exam, mix problems from different chapters rather than completing all problems from one chapter before moving to the next.

- When practicing a skill with multiple components (e.g., a sport with different techniques), alternate between techniques rather than drilling one technique repeatedly.

- When reviewing material, shuffle your flashcards rather than reviewing them in chapter order.

Check 4: Am I Elaborating by Connecting New Material to What I Already Know?

What to check: Am I actively explaining, comparing, and connecting new information to my existing knowledge, or am I trying to memorize it in isolation?

Why this matters: Information that is connected to existing knowledge is remembered better because it is encoded in a richer network of associations. An isolated fact has one retrieval pathway; a fact connected to five other facts has six retrieval pathways. Elaboration creates these connections by forcing you to think about how new information relates to what you already know.

How to apply it:

- After learning a new concept, explain it in your own words as if teaching someone else.

- Ask yourself: "How is this similar to something I already know? How is it different?"

- Generate your own examples that illustrate the concept in contexts different from the ones provided in the source material.

- Write brief summaries that explain not just what something is but why it matters and how it connects to other things you know.

Check 5: Am I Getting Immediate Feedback on My Performance?

What to check: When I practice, do I receive prompt feedback that tells me whether my answers are correct and, if not, what the correct answer is?

Why this matters: Practice without feedback can consolidate errors. If you practice retrieving information and retrieve it incorrectly, the incorrect version may be strengthened by the practice. Immediate feedback catches errors before they are consolidated and provides the correct information while the context is still fresh.

Research by Butler, Karpicke, and Roediger (2008) found that feedback after retrieval practice significantly improved long-term retention compared to retrieval practice alone. The feedback does not need to be elaborate--simply knowing whether an answer is correct or incorrect and seeing the correct answer is sufficient for most learning contexts.

How to apply it:

- When using flashcards, check the answer immediately after attempting to recall.

- When solving practice problems, check your solution against the answer key before moving to the next problem.

- Seek environments with built-in feedback: language learning apps that correct errors immediately, coding environments that show whether code runs correctly, practice exams with answer keys.

Check 6: Am I Practicing Deliberately, Not Just Spending Time?

What to check: Is my practice focused on specific areas of weakness, at the edge of my current ability, or am I simply spending time in the general vicinity of the material?

Why this matters: Anders Ericsson's research on expertise development demonstrated that improvement in complex skills requires deliberate practice: practice that is focused on specific weaknesses, conducted at a challenging difficulty level, and accompanied by immediate feedback. Simply spending time on an activity--even large amounts of time--does not produce improvement if the practice is not deliberately structured.

A chess player who plays hundreds of casual games may never improve. A chess player who studies specific opening variations, analyzes positions with an engine, solves tactical puzzles that target identified weaknesses, and reviews games with a coach will improve steadily. The total hours are less important than the structure and focus of the practice.

How to apply it:

- Identify specific areas of weakness through testing and self-assessment.

- Design practice activities that target those weaknesses specifically.

- Practice at a difficulty level that is challenging but not overwhelming--just beyond your current ability.

- Seek expert guidance (teachers, coaches, mentors) who can identify weaknesses you cannot see yourself and design targeted practice activities.

Part 3: Learning Myths to Avoid

Check 7: Am I Avoiding Ineffective Strategies?

What learning myths should checklists address? Several widely used study strategies are ineffective or actively counterproductive. The checklist should help learners identify and replace these strategies:

The learning styles myth. The idea that people learn better when instruction matches their preferred "learning style" (visual, auditory, kinesthetic) is not supported by evidence. A comprehensive review by Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, and Bjork (2008) found no credible evidence that matching instruction to learning styles improves outcomes. All learners benefit from multiple modalities (visual, auditory, hands-on), and the most effective learning strategies (retrieval practice, spacing, interleaving) work regardless of supposed learning style.

Highlighting as learning. Highlighting and underlining are among the most popular study strategies and among the least effective. Dunlosky and colleagues' 2013 meta-analysis of ten common study strategies rated highlighting as having "low utility" for learning. Highlighting is passive--it requires no deeper processing than recognizing which sentences seem important--and creates a false sense of engagement with the material.

Cramming effectiveness. Cramming (massed practice before an exam) can produce short-term performance on the exam, which reinforces the belief that cramming works. But the information retained through cramming fades rapidly--within days to weeks, most of the crammed material is forgotten. Students who space their study over time retain significantly more material at every delay interval.

Re-reading as sufficient study. Re-reading is the most commonly used study strategy and one of the least effective. Re-reading creates a feeling of fluency that is mistaken for understanding, but it produces significantly less learning than active strategies like retrieval practice, self-explanation, and elaboration.

| Strategy | Popularity | Effectiveness | Why the Mismatch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Re-reading | Very high | Low | Creates fluency illusion |

| Highlighting | Very high | Low | Passive, no deep processing |

| Summarizing | High | Moderate (if done well) | Depends on quality of summary |

| Practice testing | Low | Very high | Feels effortful, less comfortable |

| Spaced practice | Low | Very high | Feels less productive than cramming |

| Interleaving | Very low | High | Feels confusing, less fluent |

| Elaborative interrogation | Low | High | Requires effort and prior knowledge |

Part 4: Measuring Learning Effectiveness

Check 8: How Do You Measure Whether You Have Actually Learned?

How do you measure learning effectiveness? The most common error in assessing one's own learning is confusing familiarity with competence. After studying material, you may feel that you know it because it feels familiar when you read it again. But can you produce the knowledge from memory without looking at the source? Can you apply it to a new situation you have not seen before? Can you explain it clearly to someone else?

Effective self-assessment methods:

Free recall. Close all materials and write everything you can remember about the topic. This is the most honest assessment of what you actually know, as opposed to what you recognize.

Application to novel problems. Can you use the knowledge to solve problems you have not seen before? If you can only solve problems that look exactly like the examples you studied, you have memorized procedures without understanding principles.

Teaching test. Can you explain the concept clearly to someone who does not know it? Teaching requires organization, articulation, and the ability to answer questions--all of which reveal gaps in understanding that passive review does not.

Delayed testing. Test yourself not immediately after studying (when short-term memory inflates performance) but after a delay of one day or more. Delayed performance is a much better indicator of durable learning than immediate performance.

Part 5: Building a Learning System

Check 9: Do I Have a Sustainable Learning Routine?

How often should you review the learning checklist? The checklist is most valuable when it becomes a habit rather than an occasional reference. Initially, review the checklist daily before each study session to build awareness of effective and ineffective strategies. As the strategies become habitual, review weekly to verify that you have not drifted back to comfortable but ineffective habits.

Building sustainability:

- Start small. Begin with one or two new strategies rather than attempting to overhaul your entire learning approach simultaneously. Add strategies as the initial ones become habitual.

- Track adherence. Keep a brief log of which strategies you used in each study session. This tracking creates accountability and makes it visible when you revert to ineffective habits.

- Expect discomfort. Effective learning strategies feel harder than ineffective ones. Retrieval practice feels more effortful than re-reading. Interleaving feels more confusing than blocking. Spacing feels less productive than cramming. This discomfort is a feature, not a bug: the effort is what produces the learning.

Check 10: Am I Adapting Strategies to My Domain?

Should checklists differ by subject? The core principles of effective learning--retrieval practice, spacing, interleaving, elaboration, feedback, deliberate practice--are universal across domains. However, the specific implementation of these principles varies by subject matter:

Procedural skills (mathematics, programming, surgery, music) benefit from extensive practice with immediate feedback, progressive difficulty, and emphasis on automaticity (performing procedures fluently without conscious effort).

Conceptual knowledge (philosophy, history, social sciences) benefits from elaboration, self-explanation, comparison across concepts, and application to novel contexts.

Motor skills (sports, musical instruments, surgery) benefit from physical practice with expert observation, video review, and progressive challenge.

Language learning benefits especially strongly from spaced repetition (for vocabulary), immersive practice (for fluency), and interleaving (for grammar pattern recognition).

The Complete Learning Effectiveness Checklist

Core strategies (use in every study session):

- Using active recall (testing self) instead of passive review (re-reading)

- Spacing practice over multiple sessions rather than cramming

- Getting immediate feedback on practice attempts

- Connecting new material to existing knowledge (elaboration)

Advanced strategies (incorporate as core strategies become habitual):

- Interleaving different topics or problem types during practice

- Practicing deliberately, targeting specific weaknesses

- Using concrete examples to illustrate abstract concepts

- Teaching or explaining material to others

Strategies to avoid:

- NOT relying on re-reading as primary study method

- NOT using highlighting as a learning strategy

- NOT cramming all study into single sessions

- NOT assuming familiarity equals understanding

Self-assessment:

- Testing recall after a delay (not immediately after studying)

- Applying knowledge to novel problems (not just familiar examples)

- Explaining concepts without notes (teaching test)

- Tracking which strategies I am actually using (not just intending to use)

System maintenance:

- Learning routine is sustainable and maintainable

- Strategies are adapted to specific domain requirements

- Checklist is reviewed regularly (daily initially, weekly once habitual)

- Ineffective habits are identified and replaced

Effective learning is not about talent, intelligence, or the amount of time spent studying. It is about how time is spent--whether the strategies used are aligned with how human memory and cognition actually work, or whether they are aligned with how we intuitively (and incorrectly) believe they work. The gap between intuition and evidence in learning is unusually large: the strategies that feel best work worst, and the strategies that feel worst work best. The learning effectiveness checklist bridges this gap by providing a systematic framework for replacing intuitive but ineffective habits with evidence-based strategies that produce genuine, durable, transferable learning.

References and Further Reading

Roediger, H.L. & Karpicke, J.D. (2006). "Test-Enhanced Learning: Taking Memory Tests Improves Long-Term Retention." Psychological Science, 17(3), 249-255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01693.x

Karpicke, J.D. & Blunt, J.R. (2011). "Retrieval Practice Produces More Learning than Elaborative Studying with Concept Mapping." Science, 331(6018), 772-775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199327

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K.A., Marsh, E.J., Nathan, M.J. & Willingham, D.T. (2013). "Improving Students' Learning with Effective Learning Techniques." Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Brown, P.C., Roediger, H.L. & McDaniel, M.A. (2014). Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning. Harvard University Press. https://www.retrievalpractice.org/make-it-stick

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermann_Ebbinghaus

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D. & Bjork, R. (2008). "Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence." Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(3), 105-119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x

Rohrer, D. & Taylor, K. (2007). "The Shuffling of Mathematics Problems Improves Learning." Instructional Science, 35(6), 481-498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-007-9015-8

Ericsson, A. & Pool, R. (2016). Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peak:_Secrets_from_the_New_Science_of_Expertise

Bjork, R.A. & Bjork, E.L. (2011). "Making Things Hard on Yourself, But in a Good Way: Creating Desirable Difficulties to Enhance Learning." In Psychology and the Real World. Worth Publishers. https://bjorklab.psych.ucla.edu/

Butler, A.C., Karpicke, J.D. & Roediger, H.L. (2008). "Correcting a Metacognitive Error: Feedback Increases Retention of Low-Confidence Correct Responses." Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 34(4), 918-928. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.34.4.918

Oakley, B. (2014). A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even If You Flunked Algebra). TarcherPerigee. https://barbaraoakley.com/books/a-mind-for-numbers/

Carey, B. (2014). How We Learn: The Surprising Truth About When, Where, and Why It Happens. Random House. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/228582/how-we-learn-by-benedict-carey/

Gates, A.I. (1917). "Recitation as a Factor in Memorizing." Archives of Psychology, 6(40). https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1926-03760-001